Field Notes #2: Washington Park Arboretum

December 11, 2023

find non human teachers

The day itself was a mild Seattle day. The sky, a sheet of grey, and at times a light mistlike moisture hovering in the air.

The Washington State Arboretum is a familiar fixture of my college days. Almost every day, I would ride along the road that passes through it on my bike. Walls of green whished past me. Rain or shine, that was the ride I would take to the job that sustained me through my undergrad years.

At that time, "Arboretum" was just the name of this wonderful green belt. I had taken some walks through there and knew that it was filled with lots of plants. A great place to experience nature. But as someone who frequently got out of the city into the Pacific Northwest's many mountains, temperate rainforests, high deserts and high alpine landscapes, this place hardly seemed distinguished. Just another place for city slickers like me to catch a bit of nature.

Today when I returned to the Arboretum, it was just for this reason. I had just come off an fascinating but intense conversation with a friend and thought--why not rest my weary mind in this wonderful garden. By now I knew that an Arboretum is a place for trees, lots of different ones, as well as many other families of plants. I also knew that the landscapes were carefully curated by the staff--azalea way, the winter garden, and so on--all were thematically organized. I didn't know anything behind the principles of its organization, or even very much about plants in general, but I knew that the Arboretum is a living, thriving collection.

The term "collection" seems on its surface distinctly Victorian. It reminds of the old explorers setting out into the yonder to bring back new butterflies and rare specimens for their crystal conservatories. As a computer scientist, it also reminds me of a term for data types in which data are stored and organized. As an information scientist, I also know that libraries, galleries, museums, and other cultural institutions are stewards of collections. In some cases, like the library of congress, the collections are vast and encompassing. So sprawling they almost take on a life of their own, requiring ongoing maintenance and care from its staff to organize, curate, prune, augment, and make accessible.

So it all had me wondering--what happens when the collection is actually, physically alive? What happens when the collection is not only a repository of data but an open ecosystem, in ongoing interplay with itself but also with the birds, worms, rodents, native plants, humans, pets, and machines of the very same landscape? And how does thinking of data that is also life better help us understand what is "nature"?

As I entered the Arboretum, however, very little of this was on my mind. Instead I got out of my car, popped on my headphones, and began to walk.

Observational note 1: Initial walk along Azalea Way

The music pulsed in my ears. I can't recall what I was playing because I let Spotify's DJ algorithm curate the tunes. I felt strange, guilty almost, of listening to music in the park. Aren't I supposed to be absorbing the natural sounds of the wind rustling through the leaves? Or perhaps the sound of my footsteps on gravel? The latter I could faintly hear through the music, and I could also feel it against my feet as I stepped along.

The surroundings themselves were beautiful. An amply wide and flat path led me past lots of trees. Trees to my immediate right were much shorter than the coniferous ones in the distance and lining the left side of the path. They were beautiful, somewhat ornamental trees. Without leaves, they showed their structure, making them appear like strange architectural skeletons grown by some unfamiliar logic. I began to wonder about this logic: what algorithm determines how the trees grow? Is it a random walk? Surely something more purposive. I became aware that I couldn't know, but that I could discern there was some pattern as all the trees were growing in a similar fashion.

Being that the Arboretum is entirely managed, the trees were evenly spaced. Sloping up on the hill above me rose the rest of the park. It's layout is such that there is a wide promenade at the bottom of the valley, and then on the western hill there are (supremely desirable) craftsman houses while the eastern hill is home to the densest foliage of the Arboretum within which slender paths worm between the bramble of conifers and other plants. I oriented myself to this, and began paying greater attention to the plant life on the hill to my right.

It was natural beauty that was wonderfully varied. It was organized by a logic that appeared guided by the expert hand of the Arboretum's staff, and yet messy enough that it didn't feel carefully controlled. Perhaps this is what they call *managed land*?

As Azalea way reached its end, I could tell I was beginning to feel more soothed by the plants around me. Perhaps this feeling was shared by the others in the park? On this main thoroughfare occasional walkers would pass by. A couple sporting puffy jackets and beanies, rapt in conversation. A man with his shaggy white dog, entering a park via a charming old bridge shrouded in moss.

As I turned off Azalea way, towards small paths, I noticed a sign. I've attached the photo below.

In a bold red background it says:

Be Aware: Coyotes Live in the Area

Do not feed coyotes.

Do not run from coyotes.

Do act big and keep loud! -- this particular line felt somehow useful. noting it. Maybe I'll need it later if I meet a coyote. Is that the same strategy with bears?

Do keep your pets leashed to keep yourself and your furry friend safe...

*Remember, we co-exist with these animals!

This sign was itself a reminder to the park's urban, pet ladened visitors that they were entering into a new ecosystem. To me it was a welcoming sign in that it was helping learn the rules of the road of a landscape upon which I am a guest. It seemed to imply "welcome visitor, but take care to follow our rules" and by doing so establishing a boundary--an ecosystem boundary--that indicated it was an open system, humans and pets are allowed after all, but to safely flow through it one must adhere to the local customs.

Scene 2: Datafication of plant aesthetics

Taken by the plants withered in winter beauty, I began to capture them for my records as best I can. I'm no botanical illustrator (as my late cousin in law Beatriz was), nor do I have remotely access to words, or sufficient familiarity with plants (what trees along Azalea way were the Azaleas?) to capture it with writing. So a part of my observational notes are largely told through the media that I can use: images and video.

The specific contours of the plant, its texture, its wily configurations and shapes invited me to get closer and closer. As I was photographing the plant, I must have realized that, on some level, I was having a purely aesthetic engagement. And yet by seeing the plant mediated through the apparatus of my device, I could begin to appreciate it in new dimensions. As I aimed for macroscopic photos, I could bring out the textures and patterns in part because it sometimes felt easier for me, at first, to look at the screen image of the plant instead of the plant itself. The cropping of the photo helped me focus, and the color balancing, while not perfect, conveyed the complex hues that I can scarcely imagine in my mind's eye.

I felt through this activity that I was getting closer, in some subtle way to the plants, as I permitted myself to shove my camera deeper and deeper into the bramble. Walkers who passed didn't seem to mind the nature photoshoot I was having. Nor did the plants. I took care not to disturb them, to not break branches, and to try to not step on the ground cover where it could be avoided. Tuning into my surroundings this way gave me the sense that sometimes the proximity of plants to one another, like the lichen on the branch, was evidence of some kind of ecosystem, perhaps even symbiosis, that was visually legible in the surface of the plants. All of my doubt and uncertainty of what I was seeing was only leading me to feel that I simply was illiterate when it came to plants and that, were I a botanist, the data kept in the Arboretum's collection would be rather more available for me to decode, analyze, and make use of.

As I was deeply immersed in my photographic exploration of the park, I wandered into a clearing. A low, brown sign stood to the right of me. It told me I was in the Joseph A. Witt Winter Garden. And in the garden stood a man. He was tall and lean, middle aged, wearing grey work-wear pants and a Seattle Seahawks baseball cap. Not far from him was a small golf cart, and in the distance kneeled a woman over some plants, working away.

Scene 3: Roy Farrow, Horticulturalist

Noticing that the man was an Arboretum staff, I got his attention and asked him a question.

"Is the garden named after Joseph A. Witt Winter, or is it a Winter Garden? If so, what is that?"

He immediately understood me and went on to explain that Joseph A. Witt was crucial to the creation of the arboretum, and that, indeed, where we are is a Winter Garden. He explained that a winter garden is filled with plants that bloom during winter, and that the plants here are, for the most part, just getting started. He began to start talking about specific plants--whose many names I swiftly forgot--and I began to get the sense that he knew all the plants *personally*. He told me about one plant at the far end of the garden that would make the most magnificent smell. It was his favorite plant and when it's blooming you can smell it from far away. Other plants nearby had special twisting shapes that he liked. Others look dull and grey in the summer but show beautiful salmon tones in wintertime.

As we began to talk, the conversation never once strayed from plants. Every question I asked, he patiently and eagerly answered. I told him I can't even tell the Pacific Northwest Conifer's apart, and he began pointing at the trees encircling us, one by one, and telling me which was which. Douglas Fir, True Fir, Spurce, and so on. He then started walking over to one of the trees, and he showed me that if I turned over the leaf I could see little, white angel shapes beneath them. He said that he sees angels, but that I could pick whatever shape I liked. We then turned over other leaves and analyzed them, and we went on like this, talking about plants, for a while.

He recommended to me that if i wanted to learn more about plant identification, that the community colleges have great classes and he recommended Edmunds community college and a few other community colleges. He this way because you could take horticulture classes there and not worry about your grades, just getting the most out of it. When he first went, he started off taking an advanced tree identification class that assumed a lot of knowledge from the earlier classes and so he was able to get most of the material up front all at once. I told him I liked that approach, and had often used it too.

It was at about this point in our conversation that I realized that I was doing a field visit, or rather, how fortunate I was to have crossed paths with Roy. I took out my phone and began documenting some of the tidbits of wisdom he told me as I continued to ask questions and he patiently answered them. Here are my notes with, comments in parentheses, copied below:

arboretum - roy farrow

25 years a botanist

midwinter fire - dogwood everyone should have this plant

swizzle stick - orange salmon to it gets

(ways of cutting back plants)

stooljng to stump

coppicing trimmjng on yearly basis, can use for fence

[on] learning more

just jump in, visit garden, volunteer, arboretum all opportunities

[some volunteers come as a] dedicated independent gardener - train, tools, come as their schedule fits (they train them, provide tools, they come as their schedule fits)

groups come on [monday, wednesday, thursday] mornings

take a plant ID class at a community college

abies suction cut

western red cedar butterfly leaves and white

edmund’s community classes

aboriculture - teaches you whole hort program in one class

volunteer park conservatory (has a great cactus collection)

winter garden has a strong scent because there are no pollinators, have to blast (to get the attention of pollinators)

we want the plants to appear as they’re supposed to look

we only prune for safety

you notice the structure of the plants when the leaves fall off

you do what you can till something pulls you away

he was a bubble guy (referring to the UW professor who designed the arboretum, meaning that he would give staff general instructions on what should go there and they'd figure out the rest, using whatever plants, mulch, landscape etc. was on hand and could be achieved. by all accounts, its was made out to sound like a fairly improvisational process to implement his directives: a truck would show up with however many plants, and they'd just have to go from there. on the other hand, they still have access to his plans and notes and they go back to revisit them from time to time to understand what next they want to do with the gardens)

the theme of the woodland garden is fall

miller library — plants collection

plant collection owned by state, uw manages it, city manages park (an ecosystem of institutions manages the arboretum! I pointed this out to him and he said "yea, a political ecosystem" with a flat voice revealing some veiled tensions)

fan palms and cabbage palms drop their leaves on the trunk, is used as insulation, don’t wanna risk cleaning it up and killing (this was one of the most fascinating stories! basically the fan palms and cabbage palms will drop their leaves and then it acts as insulation, and if one goes to clean it up that will actually harm the plant as it cannot alone withstand the cold. it was a tale of how we must learn to carefully intervene, even with the effluence of delicate processes, because in the world of plants what might appear to us as waste could likely serve a purpose or be someone else's food, hence why they also let the leaves lie.)

don’t clean up what’s still useful, you might not know

(different kinds of root systems... I had only heard of rhizome, not corm or bulb)

rhizome

corm

bulb

underground stems to propagate (he pulled up a rhizome to show me --see photo-- I later pulled up some additional ones, trying to do it myself. he told me I could keep them and propagate them at home, but that technically I wasn't allowed to do this but he'd let it pass. wow, a gift! I wrapped them up in a AI2 (Allen Institute for AI) bandana and put them in my backpack. Now they're sitting in a jar, waiting to be propagaged tomorrow. This is what I mean by open ecosystem, humans, plants, all are entering and existing this system all the time)

underground structures store food - bloated built (to keep energy, referring here also to roots)

you talk to the plant every day , eventually get all the names

tree of heaven - trying to get rid of — invasive and nightmare to get rid of, wonderful and shallow. cut main trunk it sprouts all over. poison or take 10 years, committed team digging away and starving the root system

main host of spotted lantern fly

beautiful i love it , a real shame

ailianthus

(tree of heaven) plant report on website — bottom of website, history is there, back to thomas jefferson

“don’t hate your neighbor” many trees look like it kinda ; if we tell people it’s really bad, get it right

“have rhizomes, will garden” (I love this so much.)

End of notes

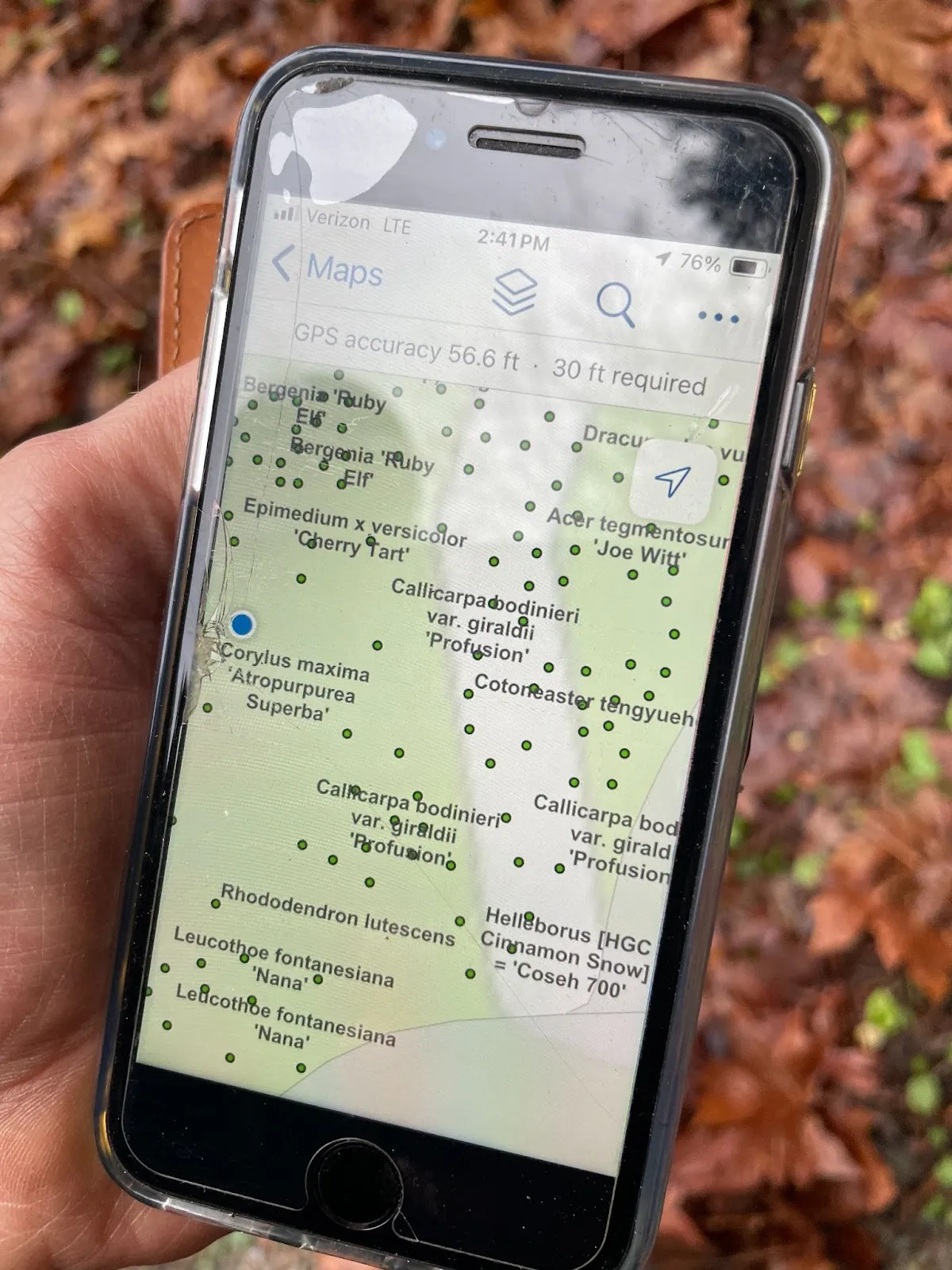

The plant that we pulled up was one that eluded Roy's ability to identify. Instead he pulled out his phone and opened a folder titled "Nature" containing apps for plant identification, invasive species, etc. He opened the identification app and crouched to point it at the ground. We tried a few angles and it still eluded him. So, in this case, the "data" in the collection was illegible to all of us. We knew it was some plant, but nothing more. (Perhaps not dissimilar from finding an errant, unmarked book in a library off of its shelf). In one last attempt, he opened up a private map made of the arboretum showing where all the plants are. Clearly a crucial digital representation to complement the on-the-ground signs and tags hanging off branches.

Talking to Roy, it struck me that this was perhaps the first time I had talked to someone who is so deeply aware and acting upon an organic, non-human ecosystem of plants. He understood the plants, their needs, their obscure, cyclical beauty. He exists as a Steward and crucial member of this ecosystem without which it would begin to, slowly, decay. With his presence, and the volunteers and institutions supporting him, he is instead enabled to cultivate a deep practical, relational knowledge cumulated over a quarter century. As he told me: "you talk to the plant every day, eventually you get all the names." And more than the names, you begin to get a feeling for their cadences, what they like, when they work well together, when they crowd out others in their proximity, the kinds of smells they make, your own taste and preference for their smells and varied beauty. And surely so much more.

Hearing how Roy has come to know the plants and how he's learned to see them, in some way, I was reminded of the quote "find nonhuman teachers." I mentioned it to Roy, and he paused, and stood in silence for a while.

Our conversation continued for some time, we briefly greeted his volunteer who had stayed half an hour later than her shift. She was smiling and radiating a joy, obviously loving the work she was doing and getting great pleasure from it.

Roy told me that he gets many different kinds of volunteer groups. Often it's a corporate group that wants to volunteer and work on some project. Some of the groups have fixed areas that they return to season after season to continue working on it. I commented that having such a sustained project must feel very satisfying for them. Other groups, like the student conservation association, do a big project on Earth day and other select projects of the year.

We were talking about a bed of ivy beneath the conifers that he needs to begin a project on, but because it's on a steep hill, he can't just get any group of volunteers to work on it. One of the problems he sometimes has is that a corporate group seemingly outdoorsy like REI will send a "computer team" out to him and that "computer people," well, one can't expect too much of them and wouldn't be suitable for this particular section of the park. I suggested that he could get the SCA youngers in there. He thought it was a good idea, but that it would be some time before he could get to it given that the SCA is already allocated to work on other parts of the Arboretum.

I was overjoyed to have had this conversation and told him that I would definitely be looking into ways to volunteer. I asked him if it would be possible for me to drop in with my brother, who does lots of trailwork and volunteered for the SCA, at the arboretum, in fact, on some day. He told me about all the forms we'd have to fill out and then get on a schedule if we wanted to volunteer. I said ok, maybe we'll just come out and walk in the park. He told me, just enjoy it, you don't always have to work.

Eventually he mentioned needing to get back to his work and we shook hands. He set off towards his golf cart and I walked onwards into the Woodland Garden.

Have rhizomes, will garden.